By now most people have heard of the tragic events of October 21, 2021 involving the actor Alec Baldwin on the set of the movie, “Rust.” In case you haven’t, a loaded handgun was accidentally used in place of a prop, and was discharged during filming of the movie, killing the camera operator and injuring a producer. The details are easily found on the internet or read about it on Wikipedia. The event resulted in the cancellation of the movie.

Firstly, and most importantly, our condolences go out to the family of the camera operator who was killed, and also the producer that was injured by the bullet.

But as project managers, we would be remiss if we didn’t ask what went wrong and how to prevent it in the future. After all, the production of a movie is a project. And on top of that, it brings up a whole pandora’s box of other existential questions that, quite frankly, if you’re not considering the things that could wipe out your project, no matter how unlikely they are to occur, a project manager isn’t doing their job.

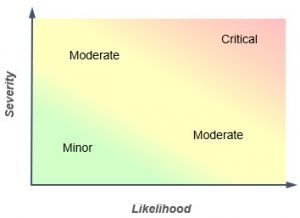

As we have all learned in project management school, project risk is comprised of two factors:

- Likelihood of occurrence

- Severity of outcome

If the likelihood is high, but the severity is low, this is an event that occurs frequently but has a small consequence. An example would be a surveyor that is allergic to bee stings.

If the likelihood is high, but the severity is low, this is an event that occurs frequently but has a small consequence. An example would be a surveyor that is allergic to bee stings.

On the other hand, if the likelihood is low but the severity is high, this is an event that could wipe out your project but is probably not going to happen. For example, an airplane crashing into to your project.

If both are high, the risk event is an important consideration.

But here’s where the rubber meets the road. The low-low scenario is a minor, low priority risk event. Conversely, the high-high scenario is usually familiar to everyone and stakeholders generally don’t hold people responsible for them except in the case of obvious negligence. Furthermore, the high-low scenario is one in which the event occurs often and is thus well known and regularly mitigated.

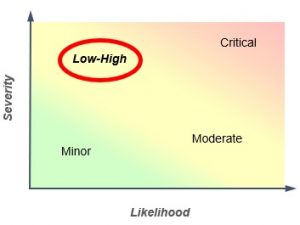

Thus, in the end, it’s the low-high scenario where the project manager earns their money. Indeed, it’s not hard to find examples of projects that fell apart after a risk event the project manager didn’t consider because they thought it too unlikely to happen.

Thus, in the end, it’s the low-high scenario where the project manager earns their money. Indeed, it’s not hard to find examples of projects that fell apart after a risk event the project manager didn’t consider because they thought it too unlikely to happen.

Without a doubt, the discharge of a loaded firearm on a movie set qualifies as one of these low-high events.

What Are Your Project’s Low-High Events?

Many of us manage multiple projects over our careers, or manage corporate departments that oversee many projects. Certainly, it doesn’t require a strong imagination to think that a catastrophic event might happen sooner or later somewhere on one of those projects, and that it would have an outsized consequence on the reputation of the project management team. Even if you manage only one project, a catastrophic event can happen and is worth at least a basic level of pre-planning.

How is there any doubt that many innocent people on the set of Rust will suffer the negative consequences of being associated with that movie for the rest of their careers.

The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) specifies the creation of a “risk register” which identifies “risk events” that can derail the success of a project. Of course, there are an infinite number of possibilities, but the risk register will specify only the most important. The first step is to define as many of them as possible so that they can be analyzed and whittled down later.

Secondly, each event is given a rating for its two underlying factors, probability and severity. This can take various formats, like a percentage (for example there is a 30% probability of rain delay which results in a 90% loss of productivity: 0.3 x 0.9 = 0.27) or an empirical rating such as 1-10 or A-C. If it’s low probability / high severity, it’s one of those catastophic events that sometimes get overlooked.

Establish Priority of Low-High Events

By nature of their rare status, these types of events are often low priorities. Risk response plans are overlooked because it is thought that the event will not happen. But this is precisely where the value lies, because these risk events, when they do happen, also expose the preparedness (or lack thereof) of the project management team.

Proper risk response planning requires that the priority of each risk event be determined relative to all other risk events. The project management team must focus on the most important risks first.

Response Planning for Low-High Events

To most people, planning for risk usually means mitigation, or reducing one of the two variables (probability or severity). But there are other ways to deal with risk, which should be considered on the same level as mitigation.

- Avoid. Eliminate the threat or protect the project from its impact. Here is a list of common actions that can eliminate risks.

- Change the scope of the project.

- Extend the schedule to eliminate a risk to timely project completion.

- Change project deliverables.

- Clarify requirements to eliminate ambiguities and misunderstandings.

- Gain expertise to remove technical risks.

- Transfer. Offload the impact of the risk to a third party.

- Direct methods: Insurance, warranties, or performance bonds.

- Indirect methods: Unit price contracts instead of lump sum (or vice versa depending on which side of the contract you’re on)

- Legal opinions

- Accept. All projects contain risk. As a minimum, there is always the risk that the project doesn’t accomplish its objective. Hence, it follows that project stakeholders must accept certain risks. Tolerating risk is a strategy like any other, and strong communication of risks to all stakeholders, and strong response plans, can be a good way to achieve buy-in knowing that there are associated rewards for project success. After all, project success is largely defined by the opinion of the stakeholders. Risk acceptance can be passive, whereby the consequences are dealt with after the risk occurs, or active, whereby contingencies (time, budget, etc.) are built in to allow for the consequences of the risk to the project.

- Mitigate. Most people think of mitigation first, but I’ve left it for last to emphasize that that there are other, often quite plausible, options. Mitigation involves taking actions to reduce the risk, for example holding safety meetings, purchasing protecting equipment, providing daily market updates, things like that.

For Low-High risk events, you could lump a group of events together that have similar features, to minimize the time involved. For example, instead of having risk response plans for hurricanes, tornados, and floods, you could have one for all extreme weather events. If it encompasses a large, highly unlikely group of events, perceived preparedness of the project management team could be achieved without alot of effort.

Catastrophic Events

Furthermore, Low-High risk events can be categorized into those that cause failure of the project, and those that don’t. Essentially, it is good practice for a project manager to think about those that are catastrophic to the project. Here are some examples:

- A large industrial project where the raw material supply is completely shut off due to geopolitical events.

- A construction project that contains a specialty product that only one (or a few) are familiar with.

- A software project that is dependent on a single point of access to a third party product.

- A project that depends on financing from one source but has not fully secured it.

- A movie that requires actors and actresses to point guns at other actors and pull the trigger.

Although the inquiry into the movie “Rust” has not yet been released (as of this writing), it is clear that there were protocols in place (let’s call them Risk Response Plans), for example:

- Prop guns (fake) were to be used where possible.

- When real guns needed to be used, an armorer was to be in charge of all weapons.

- The actor was not to point the gun directly at another human unless absolutely necessary.

Had the producers of the movie considered a bunch of low-high risk events, such as the possibility of a loaded gun entering the movie set as a prop, they may have performed small actions that could have prevented the tragedy, such as checking with the armorer, or grabbing guns and looking at it themselves.

Duration Increases Probability

Finally, since most people spend a long time in the project management field, the probability of experiencing a “low probability” event is actually not that small. That is, the longer you manage projects, the more likely you are to encounter a “low probability” event that will have disproportionate consequences to your career.

In conclusion, whatever risk response methods you choose, maybe it could be prudent to put a disproportionate emphasis on your project’s low-high (low probability / high impact) risk events. When they happen, stakeholders feel comforted by the slightest consideration during project planning, which feels “above and beyond.” It can even look good on the project manager.

And then you can sleep well knowing that the events of “Rust” won’t happen to you, but even if they do, you’ll be in good shape.

Leave a Reply