Scope issues are the #1 reason for project failure. Whether it’s scope creep sneaking in unnoticed or a poorly defined goal from the outset, projects derail fast when boundaries aren’t clear.

Project managers are seemingly always dealing with budget and schedule issues, and they always seem to have an origin in the underlying project scope. In project management, defining and controlling what’s included in a project—and what’s not—is critical to success.

That’s where a scope management plan steps in. Think of it as your project’s guardrails, keeping everyone on the same page and the finish line in sight.

What is a Scope Management Plan?

A scope management plan is the component of the project management plan that describes how the scope will be defined, developed, monitored, controlled and validated (Project Management Body of Knowledge).

It’s a roadmap that ensures everyone involved understands the project’s boundaries, deliverables, and how changes will be handled. Without it, you risk scope creep, missed deadlines, and frustrated teams.

The core of the scope management plan is the project scope statement. However, the other smaller items are equally critical to effectively managing and controlling the project scope.

How do You Use a Scope Management Plan?

A Scope Management Plan is approved by all stakeholders at the planning stage of the project, and becomes a living document which is consulted regularly by the project manager.

Project control is continuously performed by the project manager throughout the project. That means that on regular, pre-planned intervals (weekly, monthly, etc.) the project manager assesses if the scope statement is still valid and/or if changes need to be made. If there are changes required, the scope change procedures within the plan are initiated.

What are the Components of a Scope Management Plan?

A good scope management plan will have the following sections:

- Requirements

- Stakeholders

- Scope Statement

- Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)

- WBS Dictionary

- Roles and Responsibilities

- Deliverables

- Sponsor Acceptance

- Scope Control

Requirements

A proper scope identification process will allow for a requirements identification step. This is where you contact the stakeholders, meet with them if necessary, and identify and prioritize all of the external requirements the project must meet. It’s important not to miss anything. Most projects have a myriad of requirements originating from many stakeholders, and it’s surprisingly easy to miss one minor one that has an outsized ability to affect the project.

The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) includes the creation of a Requirements Traceability Matrix. Essentially, this is a tracking chart whereby the requirements from various stakeholders are given a sign-off at different stages throughout the project life cycle. For example, a landowner near a new road site might be informed of the project at the conception stage, again once the options under consideration have been tabled, and finally at the finished design stage. The requirements traceability matrix is a tracking tool that ensures the project team get the land owners sign off at each stage.

Scope Statement

The scope statement defines the project. It is the core of the scope management plan and the other components lay the foundation. The scope statement is a written description of the project scope, major deliverables, assumptions, and constraints (PMBOK Guide, 6th Edition). It states in writing what work will be part of the project and what will not, and its importance should not be underestimated.

You can’t define every nut and bolt at the beginning of the project, but it is almost always better to spend a little bit of extra time defining the scope. This practice almost always reaps rewards throughout the project.

Here is an example of a bad scope statement:

The following is the right way to build the scope statement which establishes stakeholder expectations and reduces risk of scope changes during the project:

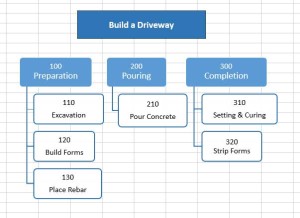

Work Breakdown Structure

Called WBS for short, the work breakdown structure is the division of the project into tasks. It forms the basis of modern project management techniques as each task is analyzed throughout the project for schedule and budget progress (called earned value management). The budget for each task includes all of the tasks resources, including man-hours, equipment, tools, and contractor costs.

Called WBS for short, the work breakdown structure is the division of the project into tasks. It forms the basis of modern project management techniques as each task is analyzed throughout the project for schedule and budget progress (called earned value management). The budget for each task includes all of the tasks resources, including man-hours, equipment, tools, and contractor costs.

It can be graphical or tabular, and can be structured in various ways:

- Project phases

- Project deliverables

- Subprojects

In it’s most basic form, it’s just a list of tasks, like this:

| ID | Task | Start | End | Budget |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Mobilize | Oct. 10 | Oct. 11 | $250 |

| 20 | Dig Canal | Oct. 11 | Oct. 20 | $3,000 |

| 30 | Pour Concrete | Oct. 15 | Oct. 23 | $5,000 |

| 40 | Clean Up | Oct. 23 | Oct. 24 | $1,750 |

| TOTAL | $10,000 | |||

WBS Dictionary

In PMBOK terms, a WBS Dictionary supports the Work Breakdown Structure. It itemizes the following things for each work item:

- Identification number/code

- Description of work

- Responsible organization or individual

This is the minimum amount of information. Other items might include start date, deadline, budget, client, milestone, or other resources required in carrying out the work item.

Roles and Responsibilities

Each part of the scope should be connected to the task lead, be it a manager, technical expert, junior technologist, or any other person on the project team. For example, design might be the responsibility of the design engineer, and drafting the responsibility of the draftsperson, and so forth.

Although all roles and responsibilities should generally by known at the project outset, responsibilities can change throughout the project, particularly if the project scope changes.

Deliverables

Most projects have physical deliverables such as such as a building, computer program, report, and so forth. But sometimes the deliverables can be non-physical like the improvement of an assembly line process, or a redesigned product. Since deliverables represent the items that the project has been commissioned to produce, all deliverables should be identified as part of the scope management plan. That way there is no confusion regarding what the project will produce.

Stakeholder Acceptance

In the PMBOK Guide, acceptance of the deliverables is a centralized part of the scope definition process. Deliverables should be identified and the work breakdown structure itemized, but the process isn’t done until the receiver of the deliverable (project sponsor, client, etc.) has seen what they will get and approved it. This does not mean they have received the deliverable, only that they approve what the deliverable will look like before the work to produce it takes place.

For example, in the case of a land development, the surrounding landowners are major stakeholders. They normally receive a scope statement at the outset of the project, which is generally nothing more than a letter indicating that they intend to develop the land. Second, they get a deliverable stating the options under consideration, and finally, the finished design. At each step of the process, their input is received.

For example, in the case of a land development, the surrounding landowners are major stakeholders. They normally receive a scope statement at the outset of the project, which is generally nothing more than a letter indicating that they intend to develop the land. Second, they get a deliverable stating the options under consideration, and finally, the finished design. At each step of the process, their input is received.

It’s a common occurrence that an owner wants something, let’s say a new bridge, and in their mind everything involved in a new bridge is included in the project. Yet the consultant who manages the project deals with many variables that are unknown and/or changing, and thinks in terms of all the things which pop up which they couldn’t anticipate in the original project inception. Let’s say a concrete plant has a malfunction and several components need to be returned, increasing the consultant’s inspection time. In the owner’s mind, it’s all part of building a bridge, but in the project manager’s mind, it’s outside the scope. This type of situation is very common and highlights the importance of strong scope definition during project planning.

Scope acceptance documents should be included in the scope management plan.

Scope Control

Identifying the scope to a minute precision is a noble activity and worthy of the utmost of a project manager’s respect, but unless there is a scope control process in place there could still be storm clouds on the horizon. Scope creep is a toxic parasite that will eat your project, and project management career, alive. It refers to the slow and steady addition of unauthorized tasks to the project, and if not monitored and controlled, can result in terrifyingly bad project issues.

Procedures should be in place to inspect and examine the scope of the project at regular intervals and important milestones. Also, since most projects have some sort of scope change during their life span, procedures should be in place to allow for efficient change management and communication.

Conclusion

Hopefully this checklist will ensure your projects don’t become part of the statistics for project failure. If you have any comments or questions, I’d love to hear from you.

Patricia Rogers Lake says

Patricia Rogers Lake says

February 25, 2019 at 5:18 pmHello Bernie

I am a student at the University of the West Indies Open Campus in Barbados and I am presently writing on Project Management and conducting a research on “The components of the scope management plan” . I researched your article and find the information very useful for constructing my paper.

I also read your bio and realized that you are well qualified for the research topic.

Regards

Pat