If there is one, single most foundational part of project management, it would be breaking down the project into manageable parts. Inability to do this well causes even the most brilliant ideas to crumble under vague goals, missed deadlines, and overwhelmed teams.

Without exaggeration, the project activity list is the DNA of your project, defining what needs to be done, by whom, and in what order. It is the blueprint for turning a sprawling vision into a clear, actionable sequence of tasks.

In this guide, we’ll walk you through the art and science of crafting a rock-solid activity list, setting the stage for smoother execution and stellar results.

Projects start with a vision of the end product which are then broken down into parts called phases and tasks. Everything else is built upon that foundation, so it should not be taken lightly. Although it seems trivial, it is one of the most important parts of a project manager’s job.

Example Activity List

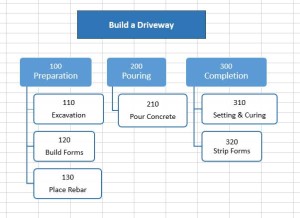

In the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK), the following might be a typical Activity List for a driveway construction project:

| Activity List | ||

| Activity No. | Name | Dependencies |

|---|---|---|

| 110 | Excavation | |

| 120 | Build Forms | 110 |

| 130 | Place Rebar | 110 |

| 210 | Pour Concrete | 120, 130 |

| 310 | Setting & Curing | 210 |

| 320 | Strip Forms | 310 |

A graphical style is sometimes helpful, but not a necessity:

Activity Attributes

The activity list also contains attributes, which identify meta-level information about the task. For example, there could be a column called “Subcontractor”:

| Activity List | |||

| Activity No. | Name | Dependencies | Subcontractor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 110 | Excavation | ||

| 120 | Build Forms | 110 | |

| 130 | Place Rebar | 110 | Jon’s Concrete |

| 210 | Pour Concrete | 120, 130 | Jon’s Concrete |

| 310 | Setting & Curing | 210 | |

| 320 | Strip Forms | 310 | |

How to Develop the Activity List

In an ideal world, you would completely define all of the project work during the planning phase. But since this is not realistic, you must get as close as possible, as time and money allows.

The activities should be defined based on the following criteria:

- The activities should be of a size and complexity that allow them to be reliably estimated. For example, it is difficult to estimate the cost for the task concrete. That’s why it’s divided into the sub-tasks pour concrete, setting & curing, etc. which can be reliably estimated.

- The responsibility for the activities should be clear-cut. For example, placing Build Forms and Place Rebar into a single item would create a situation where there are multiple responsible parties and therefore the success or failure of the activity can’t be well controlled.

- The activity should be measurable. Effective project control requires that reliable percent complete estimates are given at any time. If this is difficult to achieve, break the task down further.

- The activity should have clearly defined start and end dates.

Rules of Thumb

The above are the official guidelines for choosing activities. The following are experience-proven rules of thumb which will help you to know when you are finished decomposing:

- Activities should be between 8 and 80 man-hours of labor. This is a manageable amount. Any more, and you could lose control of the task because you are trying to manage a major subproject. Any less, and you will lose control of the project by micromanaging tiny tasks. That being said, if you are learning project management it is best to try a small project with small tasks.

- Any level should contain no more than 10 tasks per phase. This makes the phase manageable and provides valuable reference points.

- Activities should not be much longer in duration than the distance between two status points. Proper project control, according to the PMBOK, requires that earned value analysis be performed between status points, and the percent complete for big tasks inevitably gets assigned as something like 35%, 65% or 95%. This is difficult to control and project team members will inevitably exaggerate it. If you create the task to be small enough so that only 0%, 50% or 100% can be assigned, there can be no guessing as to whether a task is complete and hence project control will be very effective.

Here’s another rule of thumb. If you’re wondering whether to break down an activity further, ask these three questions:

- Is it easier to estimate?

- Is it easier to assign?

- Is it easier to track?

If the answer is yes to any one, it could be worth breaking down the activity further.

Another way to break down tasks is to ask whether the activity is:

- Well understood?

- Not well understood?

This is generally an easy distinction to make. Then, if the activity is well understood you are done. But if it’s not well understood:

- Separate out the parts that are not understood

- Determine why it’s not well understood and perform some more due diligence until it is.

Often there will be a well defined point during the project execution where an activity will transition from “not well understood” to “well understood.” Maybe some contingencies are needed to get to that point. Notice that you’ve just identified the project risks, which is the first step in project risk management.

External Information Sources

If you, or a member of your team, can reliably estimate the work on your own, this is a good situation to be in. But most often some level of extrapolation is needed from other information sources. Three sources that should be considered for every project are:

- Previous Projects. Very few projects are absolutely unique. There are always other projects from which data can be gleaned and activity lists appropriated. It’s even better when the project’s issues have been documented, because special attention can be given to activities by breaking them down.

- Templates. Every project should consider activity list templates. If none exist, let it be the first one, and adjust the list into a template for use on future projects. In our engineering company, most bridge projects are similar. Sometimes the bridge is across a road, other times a stream. But this does not change the activity list substantially, and we have a standard list we pull off the shelf and adjust to fit the situation. It ensures that nothing gets missed.

- Expert Judgment. If you have access to an expert, this is the time to use them. How should the project be divided up? What is the estimated duration? Estimated cost? Required resources? Some of those questions refer to future parts of the schedule development processes, but the activity list is the foundation.

Completion Criteria

Each activity should have written completion criteria which defines the completion of the task. It is a common occurrence that a project manager feels a task is finished but subsequently sees time and materials charged to the activity related to closing it. Often final details need to be compiled and submitted, or the task paperwork needs to be assembled and filed. Sometimes a walkthrough is necessary with a client, or a training session.

We will add another activity attribute called “completion criteria” to our activity list:

| Activity List | ||||

| Activity No. | Name | Dependencies | Subcontractor | Completion Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 110 | Excavation | Excavator is returned | ||

| 120 | Build Forms | 110 | Concrete is ordered | |

| 130 | Place Rebar | 110 | Jon’s Concrete | Concrete is ordered |

| 210 | Pour Concrete | 120, 130 | Jon’s Concrete | Concrete finishing complete and concrete covered |

| 310 | Setting & Curing | 210 | Ready for traffic | |

| 320 | Strip Forms | 310 | All work complete and Tools & Equipment put away | |

Decomposition

The PMBOK identifies a process called Decomposition, whereby the project activity list is developed starting from the top down. Start with the project name or description, i.e. “Build a Driveway” and decompose it into phases. Then decompose the phases into individual tasks. If those tasks have further sub-tasks, break it down further.

Where possible, the lowest level of the activity list should contain verbs, such as “Build Forms” instead of the significantly more ambiguous “Forms.”

WBS Components vs. Tasks

In practice, the terms Work Breakdown Structure and activity list are often used interchangeably, although the PMBOK distinguishes between them. The difference is that the WBS is a breakdown of the project to define the boundaries of the project’s scope, whereas the activity list is the basis for the project schedule. They are both decompositions of the project into tasks, and I believe there is nothing wrong with the practice of having one, single, project activity list, regardless of what you call it.

Leave a Reply