Project estimating requires predicting the future. Like ancient prophets and soothsayers, today’s project managers are experts in telling people what is going to happen.

The key to success, then, is to ensure that what actually happens is the same as the estimate. This might seem like magic sometimes, but it requires strong project cost estimation techniques.

Project Estimating

Initially, estimating takes place on the task level, that is, estimates are produced on individual tasks rather than for the whole project. This level of estimating uses three methods:

- Analogous Estimating

- Parametric Estimating

- Three Point Estimating

Analogous Estimating

If you know someone who’s walked down the same road before, their experiences are invaluable. Hence, the easiest and most accurate estimating technique involves using actual cost information from a previous project to determine an estimate for the new one.

Most organizations track actual cost data and have it available for estimating for new projects, in which case you don’t need to be a magician. However, if there is no previous cost data available, any comparable item still holds tremendous value, like how long a task took, who worked on it, and what was similar about it. In fact the best magicians use the same tricks over and over again in many different ways.

Unless the comparison project is exactly the same, adjustments will need to be made. These could occur for a multitude of reasons, like:

- Size: The task is larger or smaller than the last one

- Resources: The task requires different resources, such as people, technology, or equipment

- Product: That task is producing a slightly different product

- Quality level: The final result requires a different quality level

- Unique requirements: The task may be the same but requires different reporting or administrative functions

Parametric Estimating

When you’ve run out of analogous information, you turn to parametric estimating, which involves using a unit price and quantity to determine an estimate.

Parametric values are simply unit rates, for example,

Parametric values are simply unit rates, for example,

- It costs us $120/square foot to build a house

- We charge $2,000 per drawing to design the house

- We budgeted $165/hr for heavy equipment

Parametric unit rates originate from past experience, either internal or external, or from published industry information. The estimator must be mindful of scaling errors when there are many units, for example if the estimate is for $2/unit x 2,000,000 units, a small error in the unit rate can multiply into a larger error in the overall estimate.

Three Point Estimating

Although not a source of new information, like the other two methods, three point estimating is a more sophisticated way to determine a final estimate. It involves the determination of a Most Likely value, as well as an Optimistic and Pessimistic value. The final estimate can be determined using either:

- Triangular Distribution: E = (a + m + b) / 3

- Beta Distribution: E = (a + 4m + b) / 6

Where:

- E = Final estimate

- a = Optimistic estimate

- m = Most likely estimate

- b = Pessimistic estimate

The triangular distribution is a regular average of the three values, and is the default method. The beta distribution puts the final estimate tighter to the most likely value, so it should be used if you have high confidence in the Most Likely value and want to minimize the effect of the Optimistic and Pessimistic values.

Sometimes you have reason to believe that the distribution is skewed, for example if the potential cost overruns are greater than the underruns. In this case, the triangular distribution will skew the final estimate towards the bigger outlier.

Three point estimating is a sophisticated (but not too complicated) method that takes into account project risks. You can quantify a risk by determining the cost if the risk were to occur. For example, if the pipe breaks the repair would cost $5,000. This becomes the Pessimistic value. Similarly, you can quantify the opportunities into Optimistic values, and use either the triangular or beta distribution depending on if you wanted to create a regular (triangular) estimate or an aggressive (beta) estimate.

Accuracy

Project estimates are generally presented in three levels of accuracy:

Project estimates are generally presented in three levels of accuracy:

- Ballpark: Generally plus or minus 100%. Ballpark estimates are usually produced from analogous information from previous projects, and their only purpose is to decide whether a more accurate estimate is necessary.

- Rough Order of Magnitude (ROM) Estimate: Generally plus or minus 50%. At this level, analogous estimate information has been refined and parametric (unit rate) values used to refine the estimate. This type of estimate can be used to justify project decisions without undertaking a full estimate.

- Detailed: Generally plus or minus 10%. This estimate includes an itemized list of each expense and its associated cost.

Components of an Estimate

Estimates need to include all items of expense to complete the project. This includes:

- Labor

- Tools and Equipment

- Materials

- Services

- Facilities

- Subcontractors

- Financing

Labor

Labor can be measured in hours, days or years, and comes with an associated cost which is dependent on the skill level of the labor.

Not all labor is the same. If a task requires a carpenter, staffing it with a concrete finisher who is just as skilled at his trade is going require more time and cost more. Not to mention you might lose the concrete finisher to the competition if you do that too often.

For internal labor, an estimate of the actual cost is required. Although it may seem “free” to the project, the worker is being paid not to work on other projects. The hourly rate should be determined inclusive of salary, bonuses, and benefits. Although it may be difficult to put a number on it, this will be significantly more accurate than a zero cost.

Tools and Equipment

The tools required to complete the work can be a large part of the project, as in construction, or insignificant, such as in software development. Small items can be grouped into a catch-all item called “other” or “miscellaneous.”

Equipment that lasts for many projects must still be accounted for on a project level to ensure an accurate cost for the organization and the project. The cost of the equipment must be divided into a realistic number of projects to ascertain the actual cost to the organization.

Materials

Materials are things that are consumed by the project. For example, the carpet that gets built into a new home. Materials need to be estimated from the project specifications but don’t include a significant internal component.

Services

Nowadays you can’t do much without professional advice. Things like environmental applications, architectural design, engineering, or business advice requires a host of consultants. These consultants charge out their time, and require active management by the host organization or the cost can escalate.

Facilities

The construction of a building, warehouse space, or temporary facility required to carry out the project must be accounted for. As a minimum, most projects have to pay office rent. As with internal labor, assuming this is “free” to the project because the organization has already paid for it will not provide an accurate cost for the project.

Subcontractors

When external resources are required to complete the project work, contractors must be employed. Unless a trustworthy contractor is in place, a “statement of work” document is used to solicit bids for the work. The procurement process might even need professional advice (see above). The reason for engaging contractors are:

- Lack of internal resources

- Speed up the project completion

- Increase the quality of the final product

Financing Costs

Many projects rely on outside financing to secure their funding. This would incur interest costs. However, other financing costs include the cost of leasing, insurance, and bonding. The time value of money should be considered for project lasting more than about one year.

For projects that last more than about one year, investment concepts such as Net Present Value, Payback Period, and Return on Investment are significant and should be included in any analysis.

Overall Project Estimating

Once the project tasks have been estimated, the final act commences and the overall project budget is determined. This involves two methods:

- Top Down Estimating. Determine the phase or project level estimate first, then apportion it into tasks.

- Bottom Up Estimating. Determine each task estimate first, then roll it up into the overall project.

Bottom up estimating is generally the norm, except in circumstances where an overall project budget is given in advance and the project scope must to determined to fit into it. Usually, most projects are at liberty to determine their own budgets bottom-up-style and the organization attempts to find the funding to match it.

Top down estimating usually requires some form of bottom up as well, because it determines the correct apportionment of tasks. Since most projects are tracked on the task level, it creates problems when tasks are incorrectly estimated even though the overall project estimate is still valid.

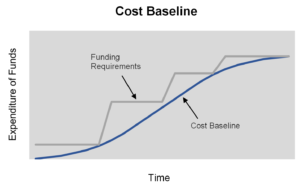

Cost Baseline

Although the tea leaves might be telling you your destiny, the exact road to the destination might be fraught with danger. The Cost Baseline shows the planned expenditure of funds over time. It requires an accurate project schedule. The project budget is one single number, whereas the cost baseline is the representation of when it will be spent.

Although the tea leaves might be telling you your destiny, the exact road to the destination might be fraught with danger. The Cost Baseline shows the planned expenditure of funds over time. It requires an accurate project schedule. The project budget is one single number, whereas the cost baseline is the representation of when it will be spent.

During the project, earned value analysis is used to track the project against the cost baseline.

Stakeholders are informed of the cost baseline and applicable funding approvals are obtained.

Contingencies and Management Reserves

To account for uncertainties between the estimating process and ultimate results, two methods are used to cover the range of uncertainties:

- Contingencies. These are added to individual task estimates to account for “known unknowns.” That is, uncertainties which are known to exist but impossible to quantify. For example, the ground conditions are uncertain and might require longer fence posts.

- Management Reserves. These are added to the overall project to account for “unknown unknowns.” That is, risks which have not occurred yet but could pop up anywhere.

As the project proceeds, the contingencies and management reserves can be reallocated since the risks accounted for did not occur.

Conclusion

These days, people who deliver projects as originally envisioned are considered magicians.

But these methods ensure that the project ends up as close as possible to the original expectations. They ensure that the project issues are minimal and that you don’t need to pull the rabbit out of the hat to have a successful project.

Leave a Reply