Every successful project—whether it’s launching a product, building a bridge, or organizing an event—starts with a solid foundation. That’s where project management fundamentals come in. These core principles guide teams through planning, execution, and delivery, turning big ideas into tangible results.

In this article, we’ll explore the essential building blocks of project management, from defining goals to managing resources and risks. Whether you’re a beginner or a seasoned pro looking to sharpen your skills, understanding these basics is the key to keeping projects on track and teams in sync.

The Project Management Profession

Project Management is a unique field in that people generally don’t choose it as an initial career path. They enter via the back door through a technical field, or they want to learn project management theory with the goal of advancing into the role. For this reason, many people who practice project management are generally not well equipped with project management fundamentals.

There is, however, a such thing as a project management career. In large construction, oilfield, or industrial projects, project management will consist of a team whose only job description is to manage the project. When that project completes, they seek out the next project to manage.

This is not the norm, however, as most projects in the world are small and must be administered by people from the related technical field.

In this post, I will provide a brief overview of project management fundamentals. A good textbook on the subject will run 400-500 pages long, but nonetheless, you can get a running start and seek out further knowledge later.

Our central reference will be the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) produced by the Project Management Institute (PMI). The PMBOK guide is generally the most widely used source of project management theory in the most parts of the world. The PMBOK can be purchased at any major book retailer, or Amazon.

Definition

Let’s start from the beginning. The definition of a project is “a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result.” Notice the following two key words within that definition:

- Temporary: It has a defined start and finish date. Some projects seem to go on and on forever, taking up space in the budget like an unwanted house pest. But eventually the project must be concluded and there will be grief if there are alot of pests to exterminate.

- Unique: It produces a product or service that is specific to that project. The product can be similar, or even exactly like, another project, but they must be two distinct products.

Organization of a Project

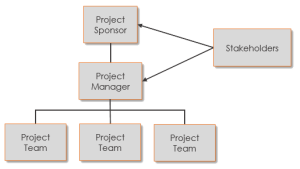

All projects have the following four roles, even if some of them are assumed by the same person:

All projects have the following four roles, even if some of them are assumed by the same person:

- Project Sponsor. One level above the project manager, this person is the organizational contact for the project. They often deal with funding the project, providing resources and support and are usually accountable for project success. They can be internal or external to the organization carrying out the project.

- Project Manager. The person that handles the day-to-day administration of the project and project team, and is directly accountable for its success. Large projects can be managed by a project management team.

- Project Team. The person or people who perform the project’s technical work, reporting to the project manager.

- Stakeholders. A party that has an interest in the work being performed by the project. This ranges from investors to affected parties to government regulators.

Phases of a Project

The foundation upon which the PMBOK is built consists of the five phases that every project goes through:

The foundation upon which the PMBOK is built consists of the five phases that every project goes through:

- Initiating. The tasks required to authorize, fund and define the project, generally on the organizational level (above the project). The organization defines a business need the project is meant to satisfy.

- Planning. The project management team define how the project will be carried out, who will do the work, how long it will take, and so forth. The planning phase should define the project in sufficient detail that all stakeholder expectations are understood.

- Execution. The project work is completed and the end product or service is achieved while secondary stakeholder requirements are satisfied.

- Monitoring & Controlling. Concurrent to the project work (execution phase) the project management team monitors and controls all aspects of the project – schedule, cost, stakeholder requirements, etc. If any part causes problems, changes to the project plan are made.

- Closing. The project has completed its product or service, and the project must be closed.

These phases are also called process groups, because each one contains a series of processes, actions, and decisions that is specific to that group.

Note that they are not necessarily carried out in chronological order. You might find yourself going back to the planning phase when project changes are required. Or if the project funding changes, you could perform tasks from the Initiating process group simultaneously with the Execution process group.

In each phase, one or more project management documents are created. For a small project, these might consist of:

| Phase | Project Documents |

|---|---|

| Initiating |

|

| Planning |

|

| Execution |

|

| Monitoring |

|

| Closing |

|

The part that is frequently underestimated is the second phase: Project planning. The Project Management Institute has suggested that planning effort be roughly 20-30% of the total work. This may seem like alot but believe me, it reduces problems further on.

In fact, the planning group is by far the largest within the PMBOK. It contains more than half of the processes even though it is one out of five process groups. The project management plan that is generated during the planning phase encompasses all of the knowledge areas, and it should be scaled to the size of the project.

Knowledge Areas

The five project phases (i.e. process groups) are roughly in chronological order, but within each phase are various parts of different “knowledge areas.” Thus, the ten knowledge areas are encountered at various times during a project.

The knowledge areas are:

- Project Integration Management. The stuff that doesn’t fit in any other category, like developing the project management plan itself, making changes to the project, etc.

- Project Scope Management. Scope is the work that is included in the project. It should be defined in the planning phase (i.e. the project management plan) and changes should be well defined.

- Project Schedule Management. Creating, monitoring and enforcing the project schedule, milestones, and completion dates.

- Project Cost Management. Estimating the project costs, and monitoring and controlling them throughout the project.

- Project Quality Management. Determining the quality standards that apply to the project, and monitoring the quality of work produced.

- Project Resource Management. Ascertaining the resource requirements of the project, acquiring them, and developing them to ensure they produce the required results.

- Project Communications Management. Establishing the communication needs of each stakeholder, and making sure they are involved to the required degree.

- Project Risk Management. Figuring out who the biggest alligators under the bed are, and how to make sure you never see them.

- Project Procurement Management. Hiring the outside consultants and contractors necessary to get the job done, and managing them.

- Project Stakeholder Management. Identifying each stakeholder and making sure they’re satisfied.

The Project Management Plan

The project management plan is the central foundation of project management, and as such we will focus a separate section on it. It is a document that gives the project manager their direction throughout the project, thereby aiding in decision making and establishing to the stakeholders how the project will be managed. Thus, it manages the stakeholder’s expectations. But most importantly, it communicates to the project sponsor, who is usually the project manager’s boss, how the project will be managed. Thus, it can also be a career-changer.

It should contain enough detail to define the project so that all stakeholders understand how the project will be managed. When project changes occur (deadlines, budgets, etc.) the project management plan should be updated. The project manager should always have a current “plan.”

This plan should be available to all project stakeholders, if not directly provided to them. But the project sponsor should absolutely be familiar with it and understand how the project is being managed.

Within the project management plan are various sections which define the project and should be updated when project changes occur:

- Scope Statement. Many projects encounter problems because it’s easy to insert small tasks into the project, veer slightly off course, perform non-important tasks, and the like. The scope statement should be detailed, including exclusions for things that might be part of similar projects (for example, does the house include a garage?). It should be set in stone and untouchable without a project change.

- Stakeholder list. All of the stakeholders in the project should be identified. But beware, the biggest problems originate with the minor, seemingly insignificant stakeholders that get glanced over because you hope you don’t ever have to talk to them. This passivity will only ensure that you eventually will.

- Task List. To govern a project effectively, it must be carved up into tasks. Each task will be assigned a duration (time) and budget (cost).

- Schedule. For small projects this could involve the specification of few project milestones, ranging up to a full graphical project schedule. For larger projects, each task is assigned a start and end date, and/or dependencies on other tasks (i.e. Task B can’t start until Task A finishes). During the project, leaving the schedule simply to gather dust is not acceptable. If the schedule is not being met, action is required by the project manager. Even if the schedule will be “crashed,” meaning more resources applied to get back on track, doing nothing is tantamount to letting the schedule gather dust on the shelf and renders it meaningless.

- Cost/Budget. Each task has a cost associated with it. When the actual costs are found to be higher (or lower), even before the task is complete, action should be taken to recover and limit propagation effects to the rest of the project.

- Quality Standards. All industries have written quality standards that apply to the products and services that are produced in that industry. Appropriate quality standards should be written into the project management plan, and quality control and quality assurance performed throughout the project.

- Project Team. It is often a part of a strong project management plan, when the project team is spelled out as well as their roles and responsibilities. Organizational charts can provide overall perspective. Additionally, the project manager, project sponsor, and other stakeholders on the organizational level could be identified.

- Vendors. Any subconsultants, subcontractors, and outside vendors should be identified. Payment methods, unit prices, or standard contracts and the like can be identified. Also, details on how they will be managed can be beneficial, such as action to be taken when they are late, submit scope changes, etc.

The Other Documents

For larger projects there are additional documents that the project manager uses to manage the project, and are appropriate for the project management plan:

- Project Charter

Optional for small projects, this document authorizes the project manager, outlines funding status, and provides an overview of the project from the organizational point of view. - Status updates

Since a project has a finite beginning and end, providing regular status updates during project execution is very important. The frequency and amount of detail depends on the project, of course, but I would suggest the existence of status updates is almost universal to good project management. - Stakeholder communications

As a minimum, the project manager must communicate with the project sponsor and project team throughout the project. On top of that, almost all projects have stakeholders who are either actively influencing the outcome, passively interested in the outcome, or actively opposed to the outcome. Correspondence that can influence the project success should be in writing, even email if possible. Keep a paper trail. - Variance analysis

This involves the calculation of, as a minimum, the cost variance and schedule variance (see Earned Value Analysis). It requires an estimate of the percent complete of each task, and the resulting variance (cost or schedule) tells you how far ahead or behind the project is. This is an excellent early warning signal for project distress, and takes only about 5 minutes once you’ve figured out how to do it via spreadsheets or project management software. That’s why I include it within introductory project management. - Project change documentation

When a change is made to the project management plan, it should be documented. For small projects this could be as simple as an “update log” within the project management plan. The important thing is not so much the format, but the underlying concept that the project has been planned out and changes to it need to be official. All project changes should be approved and signed off by the project sponsor. Change can involve the schedule (deadlines), costs, quality requirements, etc. - Final Reporting

I have yet to see a project that doesn’t need some sort of official closure. Final details of the product as-built, as-designed, or as-performed, and completion certificates for vendors’ contracts. This tends to be underrated while at the same time it tends to be highly visible to the project manager’s bosses. Do your career a favor and close the project well.

That’s it for now. Good luck on your projects and I hope this gave you a starting point in your project management adventures. If you like more information you can try our Project Management Tutorial or move on to Project Scheduling.

Leave a Reply